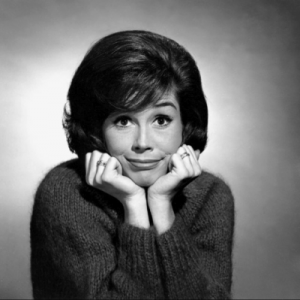

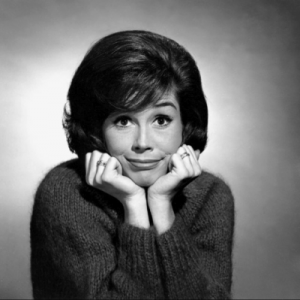

Mary Tyler Moore

Mary Tyler Moore

Over the past 15 years or so, as I’ve moved from middle age towards what sociologists call the “young old,” I’ve searched in vain for a book, blog post or website that would provide me with a reliable guide towards this process that, in my experience, is as much as a drastic developmental shift as was the experience of puberty. Aging and puberty have much in common: changes in our hormones resulting in changes in our bodies and even our voices. When I realized that the truth about aging isn’t out there, I decided to write the guide myself.

Aging has many facets. There’s the science. What is aging, exactly? There are the sociocultural aspects — what our culture tells us about who we are as older adults. There are changes to our brain (e.g., older adults experience a decline in the urge to novelty-seek). And, of course, there are changes to our faces and bodies — the changes that get most of the attention and have given rise to a multi-billion dollar anti-aging industry.

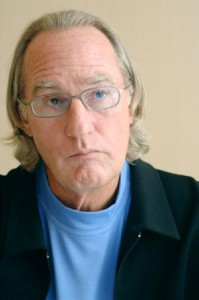

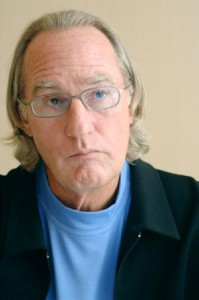

Craig T. Nelson

Craig T. Nelson

First a word about the science. What is it that happens to our bodies when we grow older? According to the experts, “We think of aging as the accumulation of random damage to the building blocks of life—especially to DNA, certain proteins, carbohydrates and lipids (fats)—that begins early in life and eventually exceeds the body’s self-repair capabilities. This damage gradually impairs the functioning of cells, tissues, organs and organ systems, thereby increasing vulnerability to disease and giving rise to the characteristic manifestations of aging, such as a loss of muscle and bone mass, a decline in reaction time, compromised hearing and vision, and reduced elasticity of the skin.” This is an important article to read, by the way, because it explains why all of the anti-aging fads (antioxidants, hormone therapies) are doomed to failure. For an even more thorough examination of aging from a scientific point of view, go here.

Whether or not one ages “well” depends on a host of factors — genetics, lifestyle and resources being the most important determinants. It’s commonly known that people whose skins have more melanin tend to wrinkle more slowly than paler humans. Inherited bone structure will also determine how your face ages, as will a host of other genetic factors. As for lifestyle, it’s also no secret that regular exercise, a healthful diet, eschewing tobacco, and making the choice not to abuse substances will help to keep you looking more robust than those who sit and watch TV all day, eating Nachos, and smoking Lucky Strikes and/or meth. However, if you’ve done your homework and read the first science-y article I shared, you’ll know that “…no one has shown that diet or exercise, or both, directly influences aging.”

So maybe at this point we should distinguish between the process of aging and the process of looking/becoming old. Because even those of us who can live, in principle, with the truth that we are all aging, can have some difficulties when it comes to the actual realities of our faces and bodies becoming old. Many experience changes that can be hard to come to terms with: thinning/lost hair; physical aches and pains; changes in our body’s shape despite exercise and diet; problems with teeth and vision even if we’ve never had those problems before. I haven’t even touched upon menopause and the changes endemic to that process. The reason I’m leaving out advice specific to increases in our Follicle Stimulating Hormone levels is that every woman’s menopause experience is so different, depending on heredity, state of mind and body, and more. Some women enter menopause in their late 30s and endure decades of misery; some women seem to glide in and out of it in their late 50s with barely a hot flash — and most women fall somewhere in between these two extremes. Having a good OB-GYN who truly listens to you can maximize your comfort and peace of mind.

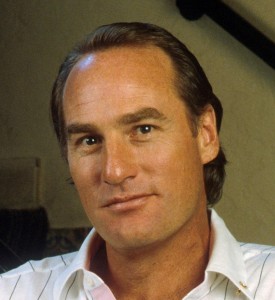

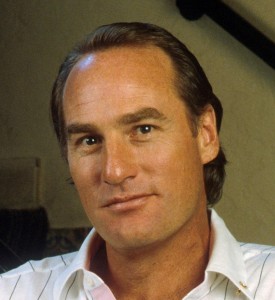

Shelley Fabares

Shelley Fabares

WHAT CAN WE DO?

As you can imagine (if you’re not yet there, age-wise), there’s a lot of panic around this business of our bodies and faces growing older. If you’re serious about approaching your 50s and 60s well-armed against the effects of looking older, here are my suggestions:

1. Be wealthy. I’m only half kidding. At the very least, have excellent health and dental insurance. But money can buy some amazing resources that will stave off some of the worst effects of aging for quite a long time. What can you buy? Products that reverse hair loss, products that may or may not make your skin look younger, hair implants, dental treatments, cosmetic procedures (more about which later), body reshaping, personal trainer, personal chef, stress-relieving retreats and massages, vaginal tightening — even contact lenses that duplicate the youthening look of limbal rings. If you have vast sums of money, you can look like Jane Fonda did at 70:

Jane Fonda, 70

What do I mean when I say “vast sums”? This, for starters. Estimates are that Ms. Fonda spent $60,800 for the initial work and shells out another $4,000 plus in annual maintenance, though that sounds low to me. To her credit, Ms. Fonda has admitted that she didn’t have the “courage” to age without plastic surgery, unlike her friend Vanessa Redgrave who is showing her real, aging face to the world without surgical enhancements.

If you can’t be wealthy, be smart about your mind and body:

2. Starting from a young age, always use sunscreen and wear a hat when you’re outside. Put sunscreen on your hands, too.

3. Starting from a young age, take care of your teeth. Brush, floss, see your dentist regularly.

4. Starting from a young age, take care of your body. Strive to be within your normal weight range. Work out regularly. Keep your muscles strong and stay flexible. Yoga, weights, aerobics, do it all as you are able (and if your doctor says okay). And sit up straight. Stand up straight. You’re no slouch so stop slouching. And don’t sit too much. Your body wants to move, let it move. Work on balance, which becomes impaired as we grow older.

5. Have regular medical checkups and all of the recommended annual tests.

6. Keep hydrated. You don’t have to be ridiculous about it, but do drink water throughout the day.

7. Create and stick to a skin care routine, and it doesn’t have to be expensive or complicated. I have pretty good skin (thanks, Mom) and since my 30s I’ve only ever washed my face with plain warm water, followed by an SPF 30 moisturizer (daytime) and Pond’s cream (nighttime). Don’t ever scrub your skin hard. Gentle, gentle.

8. Take good care of your hair (keep it out of the sun as well) and to the extent that you can afford it, splurge on a good cut and good coloring (if you choose coloring). Nothing makes a woman look older than a bad haircut and a bad dye job. Which brings me to another truth:

9. Try to dress well. If you haven’t yet found your style, it’s a good time to do so.

10. Take good care of your brain. Experts say it’s not what you do so much as that you change it up all the time. Sudoku or crosswords puzzles every day aren’t going to challenge you. Some experts even recommend that you take different routes to familiar places. The idea is to keep your brain surprised. Keep doing things you’re not used to doing — don’t let your synapses get flabby.

Even with all that, though, it’s attitude that matters most. It’s well-known that we have to maintain a sense of purpose as we advance in years. This is your path to figure out. Everyone has different religious and spiritual orientations so I can’t give specific advice. I can only promise you that having A spiritual practice, ANY spiritual practice, is going to make a positive difference in your aging. That includes having a supportive circle of like-minded (or at least interestingly different) friends with whom you can socialize and laugh with. Further, ideally the spiritual aspects of your aging journey will include a daily gratitude practice, time spent in mindfulness/meditation, time spent in nature, and time devoted to serving others. Being in gratitude will help you to be aware of the many gifts of aging that we sometimes take for granted. If we’ve been paying attention all along, we will have developed greater wisdom, insight, patience, and even a greater capacity to love and appreciate. Developing our spiritual selves is an important part of being the wise elders that we want to be. I highly recommend Lewis Richmond’s book “Aging as a Spiritual Practice – A Contemplative Guide to Growing Older and Wiser.” Because, again: if anything is going to get you through the challenges and changes of aging, it’s going to be your awesome attitude and your spiritual practice, whatever that is to you.

Bette Davis famously said, “Old age ain’t for sissies.” I heard this quote decades ago, before it had any meaning for me. Now I know the truth of it. It takes courage to embrace change of any sort, but when that change is happening in regard to our faces, our bodies, our identities, and in our lives as a whole, it takes a monumental strength. I haven’t even delved into some of the other challenges that can accompany growing older: serious illness and/or disability, or the serious illness/disability of friends and loved ones and, of course, loss of our parents, friends, even siblings. Yes, younger people suffer these losses as well, but not to the extent that we do as we grow older. Loss goes with the territory. You can age gracefully, but more than that, you will need to age courageously.

After spending the last 12 years or so developing a deeper understanding about the process of growing older, the most important thing I’ve learned is that it’s unwise to think of older/old age as just a different version of your younger life. I’ve come to understand that this is a time of life unique unto itself, unable to be compared to any earlier stage. When we are younger, we are more certain about where we get our power (for women, historically, largely through our youth, beauty and sexuality) and as we age we have to look within and elsewhere to find new sources of power. It’s at once terrifying and exhilarating. For me it involved going back to school in my 50s to get a BA and then a Master’s Degree in counseling. I’m currently on track to become a Marriage and Family Therapist — a career that will take me through my 60s, 70s, and 80s (if I am very lucky).

Robert Frost wrote, “The afternoon knows what the morning never suspected.” I could never have seen the challenges I’d face through the aging process, but I also could never have foreseen that successfully navigating them could result in such joy and enthusiasm. I’m going through a new stage of life. It’s hard, and it’s good.

Ann Clark Now-January 2015

Ann Clark Then